(SPOT.ph) Historia “is a very loaded word,” noted historian Ambeth Ocampo during the opening of the Bank of the Philippine Foundation’s art exhibit at the Ayala Museum on June 18. This is the second installment of the Obra Art Series, which aims to showcase a part of the of the financial institution’s massive art collection. Historia: Stories of Art runs until August 12.

Prof. Ambeth Ocampo traces the meaning of Historia

The rest of the inaugural address was spent digging deep into how the Philippines refers to its past. First, there is history. In the ancient dictionaries that Ocampo pored through, historia meant salita, and its root word had to do with narrative or telling stories. He had also found the word "historieta," which was translated as “munting salitang walang kasaysayan,” or small words without meaning. (Incidentally, historieta also means comics in Spanish. Make with that what you will.)

Then there’s "kasaysayan," which comes from two important concepts: Salaysay or story, and saysay, which means sense or meaning. History is not just about the past. Kasaysayan is a story that bears weight and has meaning. “Kasaysayan,” emphasized Ocampo, “is a story relevant to us today. We need to understand the present and move on to the future.”

Foreground: "Bunong Braso" by Bert Edlagan; Background: "Mutya" by Jaime De Guzman and "Batang Magdaragat" by Jose Blanco

The past that the exhibit wants us to consider is necessarily framed through the Bank of the Philippine Islands’ (BPI) own storied existence, 166 years all told, since its founding as the Banco Español Filipino de Isabel II in 1851. Along the way, there were various mergers and acquisitions that allowed the bank to amass some 900 pieces of art, the bulk of which the Ayala Museum has on a long term loan, 54 of which are currently featured in Historia.

To help the viewers understand this journey from the past to the future, the curatorial team led by Ken Esguerra selected maps, prints, paintings, and sculpture from the 19th century up to the modern art period. If we are to understand ourselves and our country through these artworks, the decision to include mostly figurative works certainly helps. Think of it as an ancient, analog version of the very popular Humans of New York—Humans of Las Islas Filipinas. Who are we as a people as seen by our artists? What do we wear, how do we spend our time, what are our hopes and dreams?

Prints as Yesterday’s Photographs

The exhibit opens with a printed map of the Philippines made by Antonio Zatta & Sons in 1785, followed by a series that showed people from the 19th century. Before the advent of photography, prints functioned as visual records. They were called tipos del pais, literally “types or scenes of a country.” These prints were also popular as souvenirs, like 18th-century Pinterest boards that showcased social status, jobs, and outfits of the day—a handy illustration of the people one encountered in their travels.

"Tipos Filipinos" by Ortego and Thomas Carlos Capuz

Take for example the work by Ortego and Thomas Carlos Capuz, “Tipos Filipinos—Mestiza Española. Mestizo Español.” The print features a woman leaning against a side table, not too far from a dandy with his embroidered Barong Tagalog, a hat, and cane. Here, “Filipino” originally meant “a person of Spanish descent born in the Philippines.” Then there’s the descriptive “mestiza” and “mestizo,” which implied that they were of mixed blood.

"Islas Filipinas: India Chichirica" by F. Muñoz and and J. Llerena

Another interesting example is “Islas Filipinas: India Chichirica” by artist F. Muñoz and lithographer J. Llerena. The first part denoted where the person comes from. “India” meant that the woman was a native or a local as opposed to the previously mentioned mestizos. The woman is dressed in elaborate baro at saya, facing the shore—there were palm trees—and yet she is flirtatiously turned to us, all the while holding aloft an abanico and a handkerchief in her right hand. The “chichirica” in the title should indicate her tribe, but as far as we know, there is no tribe called by that name in the country. However, chichirica is the name of a flower, the Madagascar periwinkle, something very abundantly found along sandy shores. So this is a woman whose cultural group is found near the beach. But a further search finds that chichirica is also called “old-maid.” A light bulb moment: Could this local woman be unmarried, a 19th-century matandang dalaga, consciously flirting for one last chance at coupling?

History as Told by the Maestros

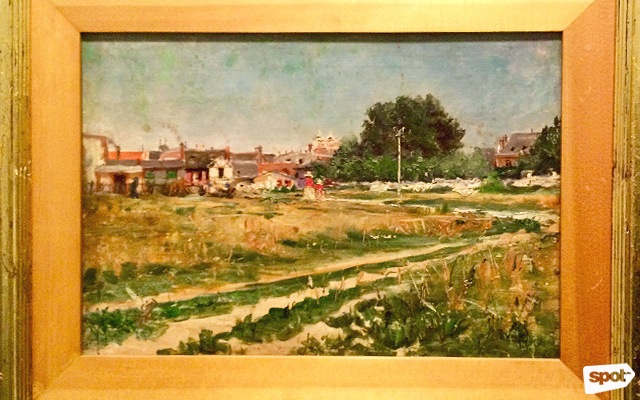

If one talks Filipino masters, the names Juan Luna and Fernando Amorsolo are not far behind. Luna is known for bringing honor to the country for winning the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes with his “Spoliarium” in 1884. He signifies a shift in the European style, at the onset of the Industrial Revolution, as seen in “Grand Canal, Venice.” But in Historia, we are also given rural Lunas. There is “Harvest Scene,” showing farm workers toiling in the middle of the field, a woman in a bright red dress in the middle stealing your attention. There’s the undated “Country Scene by the Road,” which features rows of farm vegetables in the foreground, a cluster of houses and low buildings farther back. You still get a European style slice of life, but through an Impressionist filter.

"Harvest Scene" by Juan Luna

"Country Scene by the Road" by Juan Luna

At the other side of the exhibit is a set of six tightly guarded Amorsolo pieces, which aren't allowed to be photographed. What’s notable is that this is not your usual Amorsolo, he of the golden hour and smiling maidens. There are two historical works from 1959: “Mactan,” which features the battle which shows an early resistance against the Spaniard, and "Galleon Trade," which shows Westerners exchanging goods with the locals.

Then, perhaps the pièce de résistance: A version of the “Spoliarium,” with a gladiator being dragged away from the arena, disappearing into the shadows, but it’s much smaller here, of course. It was signed “Lvna-Roma 1881” and then “Capiz par FAmorsolo 1939.” It’s the ultimate homage, from Amorsolo to Luna, from one Filipino master to another.

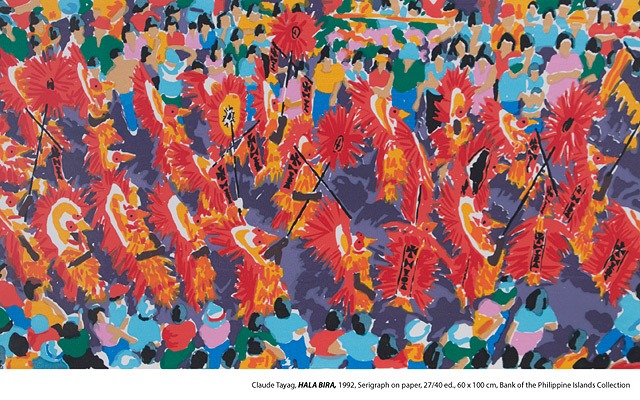

"Hala Bira" by Claude Tayag

Elsewhere in the exhibit, particularly in the post-war pieces, we see workers, farmers tilling the land, market vendors, children playing luksong-kalabaw, fishermen carrying their nets, celebrants shouting “Hala, bira!” at the town fiesta. They are done in the dominant styles of their day, but still distinctly Filipino. We’ve seen Luna doing Amorsolo-type idylls, and Amorsolo trying his hand at the European grand style. Maricris San Diego, executive director of the BPI Foundation, sums the exhibit best: It’s an “introspection on how far we’ve come as a country.”

Historia: Stories of Art runs until August 12 the Ayala Museum, Makati Avenue corner De La Rosa Street, Greenbelt Park, Makati City. For more information, visit Ayala Museum's website.

Post a Comment