(SPOT.ph) Weave through the narrow streets of Intramuros, and you will eventually stumble upon the behemoth landmark that is the Minor Basilica and Metropolitan Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, or as it is more commonly known, the Manila Cathedral.

Greeting you on Sto. Tomas street, across from the lush urban oasis of Plaza de Roma, is the church’s unmistakable façade. Wide stone steps lead to the imposing archways of this popular tourist stop. Once inside, marble floors and columns, high ceilings, and detailed iconography offer a remarkable blend of sanctity and opulence. All at once, the Manila Cathedral manages to be both an important religious hub and an architectural marvel. More than anything, however, what this edifice offers visitors—regardless of their beliefs or architectural knowledge—is a strong sense of history. In fact, its history is described as “not only a story of the Church, it is also a story of Intramuros, a story of Manila, a story of the Philippines.”

True enough, the humble beginnings of the cathedral go as far back as the recorded history of our nation’s capital city. In 1571, a Spanish Conquistador named Miguel Lopez de Legazpi allocated a piece of land for a church. The church was to be named La Purísima Immaculada Concepción—and it is where the Manila Cathedral stands today.

[BigImage:{"caption":"Eight bronze panels by Italian sculptors Alessandro Monteleone and Francesco Nagni dominate the façade of the Manila Cathedral.","photographer":"Vincent Coscolluela","image":"https://images.summitmedia-digital.com/newsroom/longform/images/2018/08/03/manila-cathedral-LRG-6.jpg","illustrator":""}]

Always Rising From the Rubble

Of course, the cathedral we know now is not at all like the original. As most structures in that era, the first church was built with materials such as nipa, wood, and bamboo—all of which were highly flammable. As a result, when a fire razed Manila a decade later, it burned the church in its wake. Learning from their mistakes, a second cathedral of stone was built 20 years after the original. Unfortunately, just a few years later, it would be destroyed by an earthquake.

The cycle of rebuilding and destruction by earthquake would repeat over the next couple of centuries. While each new version of the cathedral always seemed to come crumbling down, another would also invariably be rebuilt and redesigned to fit the architectural trend of the day. The 1614 cathedral upgraded the original design to have naves, chapels, and altars. The 1751 version was inspired by the incredibly ornate Baroque structures of Italy. Meanwhile, the 1858 rebuilding of the cathedral employed Neoclassical features that emphasized symmetry and domed roofs. Over the centuries, the cathedral’s constant rising from the rubble would echo the various revolutions that shaped the nation, making it an apt symbol of Filipino survival and adaptation.

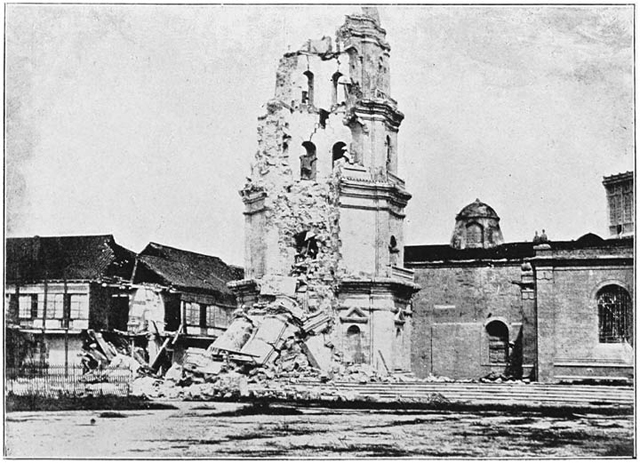

The penultimate cathedral rose in 1879. Architect Don Vicente Serrano y Salaverri employed a Romanesque-Byzantine design, which is characterized by its use of arches and religious iconography. In addition to the more geometrically complex design, what made this seventh cathedral unique was its materials. Instead of exclusively using stone, the architect made use of iron, sheathing the molave columns in the metal in order to make the structure more durable. The ornamentation was also given a lot of thought. Gildings, sculptures, and frescoes—which were commissioned from Italian artist Giovanni Dibella—adorned the interior and exterior of the church. And the stained-glass windows illuminated the cathedral with a wash of color. The result was a distinguished grandeur that cemented the church as not just the first, but the premier cathedral of the nation.

[BigImage:{"caption":"The right nave has six chapels while the left nave has two chapels and the cathedral's baptistry.","photographer":"Vincent Coscolluela","image":"https://images.summitmedia-digital.com/newsroom/longform/images/2018/08/03/manila-cathedral-LRG_3.jpg","illustrator":""}]

Standing Tall Through the Revolution

It is this version of the cathedral that ushered the Philippines into modern-day independence. The church was even an integral part of the discussion surrounding Jose Rizal’s revolution-inciting novel, Noli Me Tangere. Whereas many of Rizal’s contemporaries criticized the novel as being anti-Catholic, there were some priests—notably Father Vicente Garcia, a resident theologian at the Manila Cathedral—who defended the controversial work. Into the era of American occupation, the edifice and its congregation continued to stand tall. While there was a sudden surge in non-Catholic faiths during this colonial shift, the Manila Cathedral was left largely unchanged. “Despite the strong foothold that Protestantism and the Aglipayan Church gained during the early years of the 20th century,” say the cathedral’s historians, “the Catholic Church would remain steadfast.” And it is this steadfastness that would help it overcome what was about to be the worst of its fates.

When yet another earthquake shook the city at the turn of the 20th century, the cathedral was partially destroyed, losing its bell tower for many years. However, it wasn’t until 1945, when it was mercilessly bombarded during World War II, that the church was practically turned to dust. What remained of its famous façade was the stained-glass rose window atop the main entrance and the three receding arches where the front doors stood. In fact, most of the clergy wanted to let go of the historic location and move the cathedral to Mandaluyong. But Archbishop Rufino Santos put up a fight. Not a lot of people agreed with him but the “cathedral ruins were left to stand in place, still untouched by the bulldozers that leveled off most of the ruins of Intramuros.”

What came out of those ashes would be the Manila Cathedral we know today. Designed by Fernando Ocampo, it is inspired by Serrano’s original design, but with a Neo-Romanesque twist that blends Renaissance and modern styles. It harkens back to its grand past with features like marbled surfaces, a new bell clock tower, and beautiful mosaics. But it also looks to the future with its attention to functionality and durability. Ocampo wanted to maintain the beauty of cathedral, while further correcting its past flaws. And he succeeded. Even Pope John Paul II took notice of the cathedral, elevating it to a minor basilica in 1981.

[BigImage:{"caption":"An exhibit is currently on display to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Manila Cathedral's rebuilding after the war.","photographer":"Vincent Coscolluela","image":"https://images.summitmedia-digital.com/newsroom/longform/images/2018/08/03/manila-cathedral-LRG_2.jpg","illustrator":""}]

Looking Into the Future

Ocampo’s foresight lives on. Although this eighth cathedral has, thankfully, not collapsed despite having lived through several typhoons and earthquakes, the church has continued to invest in renovations. From 2012 to 2014, it closed its doors to rehabilitate its structure and design. The renovations included skeletal changes, such as repiping the plumbing and relocating electrical wires, to more decorative upgrades such as landscaping the Cathedral Gardens and installing new light fixtures.

Today, the edifice is both breathtaking in its elegance, as well as dependable in its stability—surpassing, by all accounts, its former glory. If the Manila Cathedral is a symbol of Filipino resilience in the face of adversity, we can learn a lot from the building’s latest evolution. One lesson is that there is beauty to be found in the coming together of different perspectives and experiences. Another is that sometimes structural damage requires a major overhaul. And last, but certainly not least, is that confronting our history—especially our mistakes—is an essential step to protecting our future.

[ArticleReco:{"articles":["73285","71667","69874","69962"]}]

Post a Comment